San Francisco's Urban Castle

/Julius Castle at 302 Greenwich Street: Landmark #121

2012 Photo Credit Chris Carlsson

How did this urban castle come to be? It all began on March 20, 1923 when Julius Roz, a local Italian restaurateur, began work on the castle-like structure perched on Telegraph Hill.

A Colorful History

The story begins in 1886 with the cliffside site as the location of Michael Crowley’s two-story grocery store. Years later, the John Mini family built their home there only to have it destroyed by a fire around 1918. In 1924, less than a year after construction on the Castle began, food service was underway. A thus established Julius’ Castle as one of the oldest San Francisco restaurants at its original location with its original name.

With Julius Roz’s collaboration, civil engineer and architect Louis Mastropasqua designed this amazing structure. Combining fairytale elements, such as pointed arched windows and medieval-style battlements on the upper balconies, a mix of Gothic Revival and Arts-and-Crafts influences lived side by side. Interior wood paneling was reputedly purchased by Roz from the city’s 1915 Panama Pacific International Exposition. The words “Julius’ Castle” on the redwood facade were added by Mr. Roz in 1928. A legend was born!

At the time, Montgomery Street was little more than a dirt trail wide enough for one vehicle. Because the street was so narrow, a turntable was installed in 1931 at the dead-end in front of the castle for employees to turn patrons cars around to parked them. During Prohibition, Julius’ Castle became a speakeasy for the carriage trade. Its patrons watched the Bay Bridge being constructed and completed in 1936. Regulars also witnessed the apparition of Treasure Island as it was dredged from the bottom of the bay for the World’s Fair of 1939-40. They also saw the wartime fleet moving in and out during World War II.

When Julius Roz died in 1943, the property passed through several owners including music promoter and restaurant owner Jeffrey Pollack (Nick’s Lighthouse). Before Pollack acquired it in 1980, the hillside icon gained landmark status. For 26 years, the gregarious proprietor hosted an intoxicating mixture of celebrities from entertainment, commerce, and politics. According to Pollack, table 34 was the for the city’s mayors. Huey Lewis, Journey, Robert Redford, Sean Connery and local characters, Melvin Belli and Herb Caen, were just a few of his loyal patrons. Even thieves appreciated the castle, when, in 1986, they stole its most expensive cases of Bordeaux from Pollack’s wine cellar.

Today, its current owner, Paul D. Scott, waits in the wings, poised to rouse the sleeping beauty. An attorney by trade and resident of Telegraph Hill, Scott purchased the property in 2012. He moved to the neighborhood in 1995 and dined at Julius’ Castle on Christmas. It was love at first sight. “There was a wow factor as you took in the view,” Scott recalls. “The interior was old-school, and the combined effect was unique.”

Julies Castle 1940s

Proprietor, Julius Roz

Julius Roz July 29, 1928

Julis Roz was born in Turin, Italy, around 1868. He arrived in San Francisco in 1902, working in various North Beach restaurants as a bus boy and waiter. Later, he became manager of several eateries, including the Dante Restaurant at 536 Broadway. At Julius’ Castle, he was all things to the restaurant: buyer, chef, and maître d’. A 1939 city guide comments on Roz’s cooking: “To taste his fish sauce supreme, his tagliarini and his banana soufflé is to have a glimpse of an epicure’s heaven.”

He was friends with many other local business persons and residents, including artist, newspaperman, and owner of the “Compound,’’ Harry Lafler. This “colony” consisting of five or so artists cottages was just across the street from Julius Castle. Thus Roz’s association with Bohemian North Beach.

Roz lived in the apartment above the restaurant with his wife, daughter and two dogs, from which he was inseparable. Elmer Gavello, of Lucca’s restaurant, describes seeing Roz with his dogs. “I’ll never forget him driving down Union Street in North Beach in a yellow Chrysler Imperial convertible. He always had the convertible’s top down and two beautiful collie dogs in the rumble seat, which had its own windshield and side windows to keep the wind off the dogs.

“…Should you get lost on the way up the hill, the small boy by the roadside will give you directions as only a small boy can. Many Italian eateries display their national colors of red, green and white. Here you can eat them in the form of red, green, and white tagliarini. As you arrive, and during your meal, Sandy will greet you with a smile and tail wag as Sandy is a collie dog. He will ask to play with you. Sandy has played with such celebrities as Jackie Coogan, Lon Chaney and Douglas Fairbanks. Yes, indeed, your host Julius Roz, has received radiograms from ships at sea on their return, asking that reservations be made for passengers as soon after their ship docks as is possible. Lunch from 12 to 2, $1.50 — Dinner from 6 to 9, $2.00.””

The Architect, Louis Mastropasqua

Louis Mastropasqua was born in Brescia, Italy, near Milan, in 1870. Graduating in 1899 from the Italian Royal Polytechnic School, he specializied in civil engineering and architecture. He studied architecture and art during his travels in Japan, China and Africa before his 1902 arrival at San Francisco. He didn’t speak any English, but quickly learned the language and established himself. He was believed to be an architect in the Italian community, especially after the building boom following the 1906 earthquake and fire. In the 1923 Crocker Langley City Directory, his office address at 580 Washington Street was listed as architect and civil engineer professional location.

Charles Bovone House 68 Macondray Lane Built 1893

Architect Louis Mastropasqua designed this small set of apartments, which was originally a residence. The design combines Colonial Revival elements (curved bay, modillioned cornice and general plan) and Craftsman elements (natural shingle cladding, the flared bay and the lost window-surrounds).

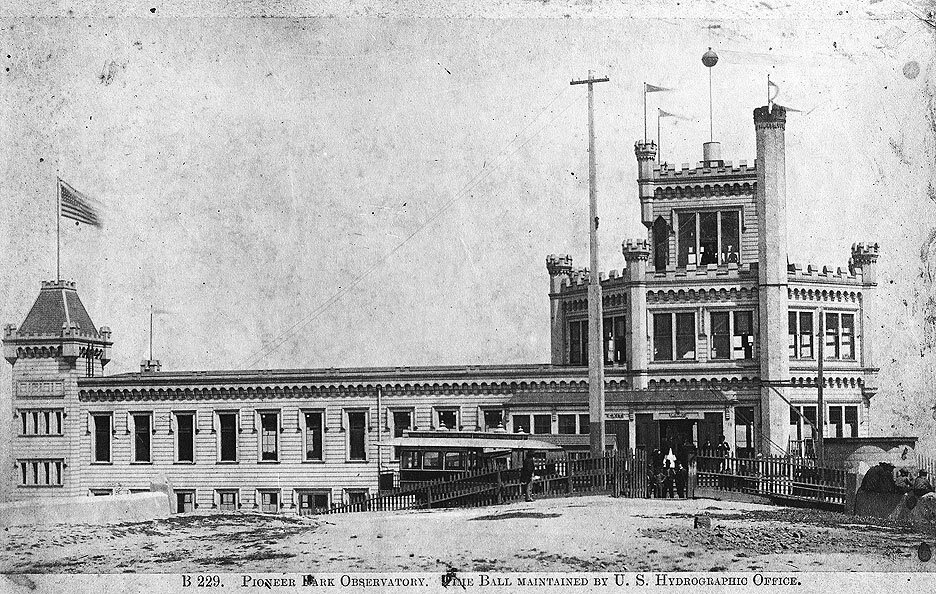

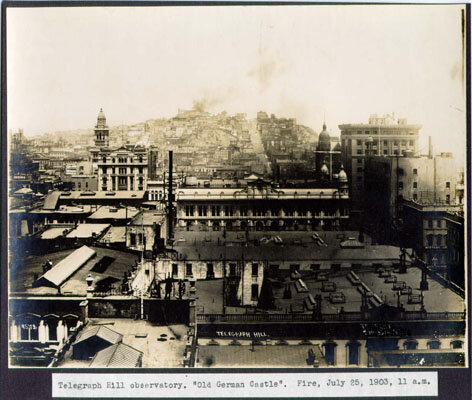

Layman's "German" Castle

Historic records indicate Mastropasqua’s collaboration with Roz on the unique design of the Castle. It was, in part, inspired by Frederick O. Layman’s wooden castle, which had stood nearby atop Telegraph Hill between 1883 and 1903. Layman built the “German” castle as a business venture and cable car terminal for his proposed observatory and restaurant. Both the cable car line, whose operations ceased in 1887, and the castle became known to residents as “Layman’s Folly”.

The structure was destroyed by fire in 1903. As Roz and Mastopasqua had arrived in San Francisco from Italy in 1902, they were able to ponder the first “Castle” on Telegraph Hill. Apparently, this gazing was inspirational, and twenty years later Julius’ Castle was created.

Film Noir

“The House on Telegraph Hill” – 1951. 20th Century Fox, Director: Robert Wise

According to film archives, 20th Century Fox used the front of Julius’ Castle in this movie. Creative changes to the structure’s image were made, so that it would look like the entrance to a stately home. These alterations to the exterior were created by building a facade around the castle.

“The Raging Tide” (1951) Universal International Pictures, Director: George Sherman

One scene from this movie shows Shelly Winters running out of Julius' Castle, pausing on the entrance steps for an emotional dialogue. City lights are the backdrop. In another scene, Winters is having brandy at the bar in Julius’ Castle talking to a bartender.

Epilogue

According to Eater SF, Julius’ Castle plans to open its doors late this year. Right now Scott is interviewing candidates, some of whom have “more of a footprint in managing restaurants” than others. “But we’re not limited in our thinking,” says Scott. He’s casting a wide net. Anyone he works with will have to be open to tackling the project as “a consultant/management entity,” and will have to “respect the history of the building.”

“Because I own the building, and I am also in the neighborhood,” Scott says, “I am very sensitive for it to continue to fit in the neighborhood as well as fill its traditional role in San Francisco.” In other words, folks hoping to open a white wall/blonde wood/minimalist spot should seek greener pastures.

Once he finds his operator, Scott says that it will be full steam ahead to finalize plans for the interior and figure out a suitable menu. “Things always take longer than you expect,” Scott says (a phrase that should probably be embroidered on the San Francisco city flag). “But if all goes well, we should open some time next year, and people can start making memories with us all over again.”

Let’s HOPE!!!!