Untangling the History of Christmas Lights

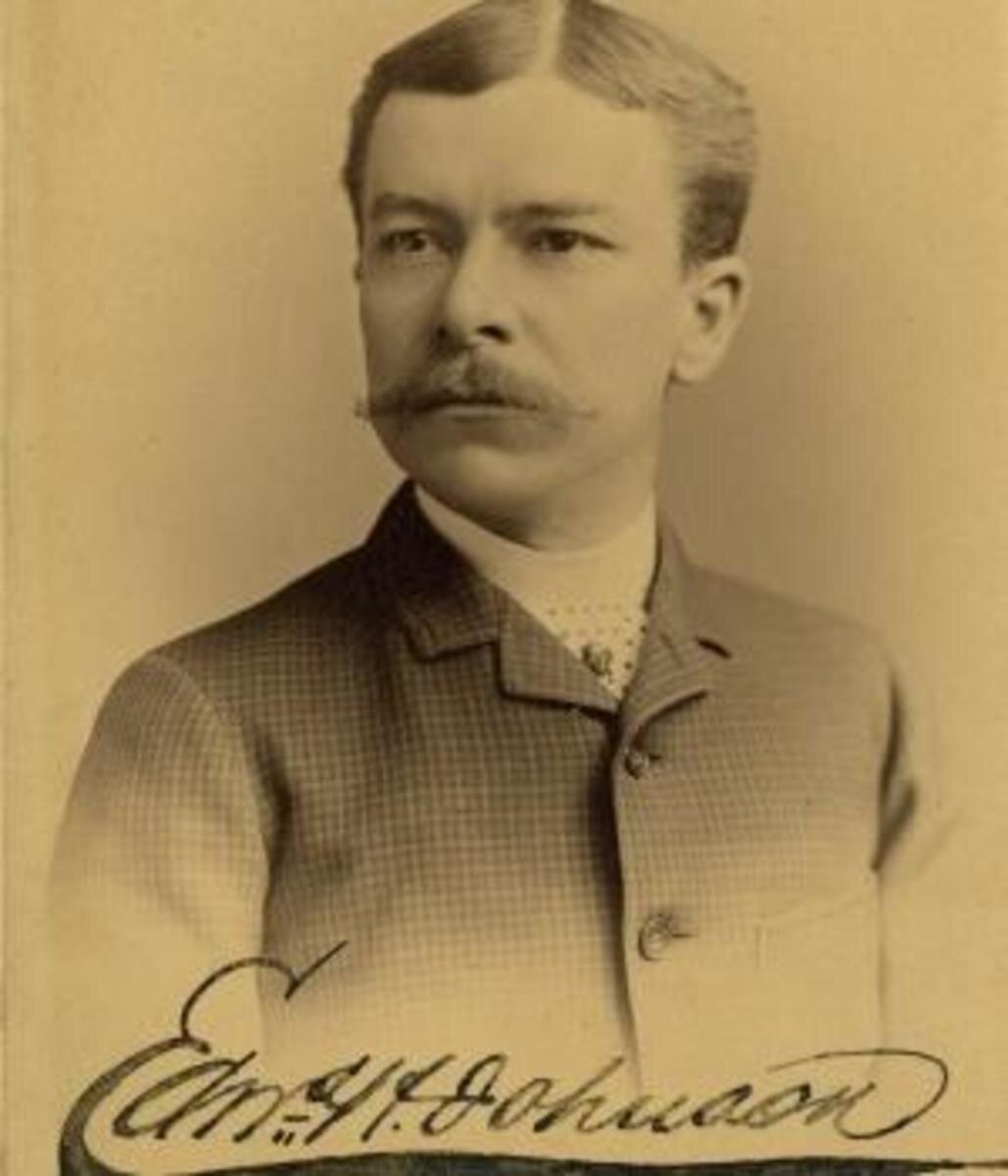

/Edward Hibberd Johnson not only added flash and color to Christmas trees when he introduced electric lights in 1882, he saved lives in the process.

As Christmas approached in the waning days of 1882, Edward Hibberd Johnson joined his fellow New Yorkers in decking the halls. Then as now, Yuletide traditions ran deep, and the 36-year-old once again undertook the annual ritual of decorating the parlor of his Manhattan home with a majestic evergreen. For this particular Christmas season, however, Johnson decided to freshen the cherished holiday tradition with a state-of-the-art innovation—electric lights.

Nearly three years had passed since Thomas Edison demonstrated the first practical light bulb, and few people were better acquainted with the emerging electrical technology than Johnson, the Wizard of Menlo Park’s trusted business associate. As a manager of the Automatic Telegraph Company in 1871, Johnson had shrewdly hired the 24-year-old Edison, but the whiz kid proved so brilliant and entrepreneurial that in short order their roles reversed and the boss became an employee for the famed inventor. Johnson worked as a vice president of the Edison Electric Light Company, and he was chief engineer for the electric generation system that Edison had unveiled in lower Manhattan that September.

Now at Christmastime, Johnson prepared to make some history of his own. For centuries—according to some folklore all the way back to the 1500s when Protestant reformer Martin Luther wished to replicate the wintertime sight of stars twinkling among the evergreens—people had used wax candles to illuminate their Christmas trees. The candles may have been beautiful, but they were obviously a huge fire hazard. Every year as year the holiday approached, without fail newspapers printed tragic stories about Christmas trees accidentally catching fire and houses burning to the ground, sometimes with deadly consequences.

By replacing candles with electrical lights, Johnson not only greatly reduced the risk of Christmas trees going up in flames, he added flash and color as well. According to a reporter from the Detroit Post and Tribune who visited the home of Edison’s right-hand man, 80 brilliant red, white and blue hand-wired bulbs “about as large as an English walnut” lit up Johnson’s Christmas tree. An additional 28 lights sparkled on two wires mounted on the ceiling.

Johnson’s electrically lit tree was revolutionary—literally. It spun in a circle six times a minute on a little pine box as its lights flashed in “a continuous twinkling of dancing colors.” An electric current drawn from Edison’s main office powered the lights and the crank that rotated the tree. “I need not tell you that the scintillating evergreen was a pretty sight,” gushed the newspaper reporter. “One can hardly imagine anything prettier.”

Unbeknownst to Johnson, he also launched the annual Yuletide tradition of trying to one-up the neighbors with dazzling Christmas light displays. Once electrical power spread to Manhattan’s Gilded Age mansions, the city’s prominent socialites coveted the novel lights to showcase their Christmas trees at their ornate holiday parties. Those first bulbs, however, lacked screw-in sockets and required the tedious process of wiring each lamp individually, a task that few had the knowledge or time to undertake. As a result, members of high society spent as much as $300 per tree to hire electricians to install lights on their conifers and be on call in case a bulb burned out or broke.

“High society spent as much as $300 per tree to hire electricians to install lights on their conifers and be on call in case a bulb burned out or broke.”

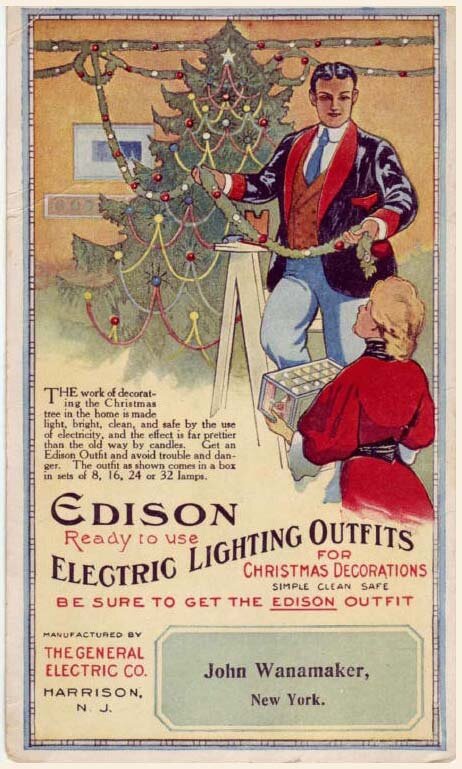

The White House Christmas tree became electrified in 1894 when President Grover Cleveland’s daughters were delighted by the evergreen that the Wheeling Register described as “very beautifully trimmed and decorated with tiny parti-colored electric lamps in place of the old time wax candles.” For most of the country, however, candles still remained the primary means of illuminating trees because of the limited availability of electric power and the cost and hassle of the Christmas lights themselves. That began to change at the turn of the 20th century when the General Electric Company started to produce and sell electric Christmas lights that did not require the services of an electrician to wire. The company accentuated the safety advantages of electric lights in their advertisements in popular magazines of the day such as The Saturday Evening Post and Harper’s Bazaar. “No danger from the lights on Christmas trees when Edison Miniature Lamps are used,” boasted the copy of one ad next to a dramatic drawing of a candle-lit tree engulfed in an inferno.

In 1903, General Electric began to offer Christmas lights in eight-lamp strings, called festoons, that featured pre-wired porcelain sockets, miniature glass bulbs and a screw-in plug that attached to a wall or ceiling light socket. The $12 price for a three-festoon set was beyond the reach of most consumers, but department stores in some cities made the lights available for rental for $1.50.

By the 1940s when electrification had become standard in rural America, electric lights had replaced wax candles on most Christmas trees, and the danger of trees bursting into flames had been replaced by the annual frustration of untangling gnarled webs of Christmas light strands. For that, thank Johnson, the man who has been called the “Father of Electric Christmas Tree Lights.”