Cold cuts at eye level

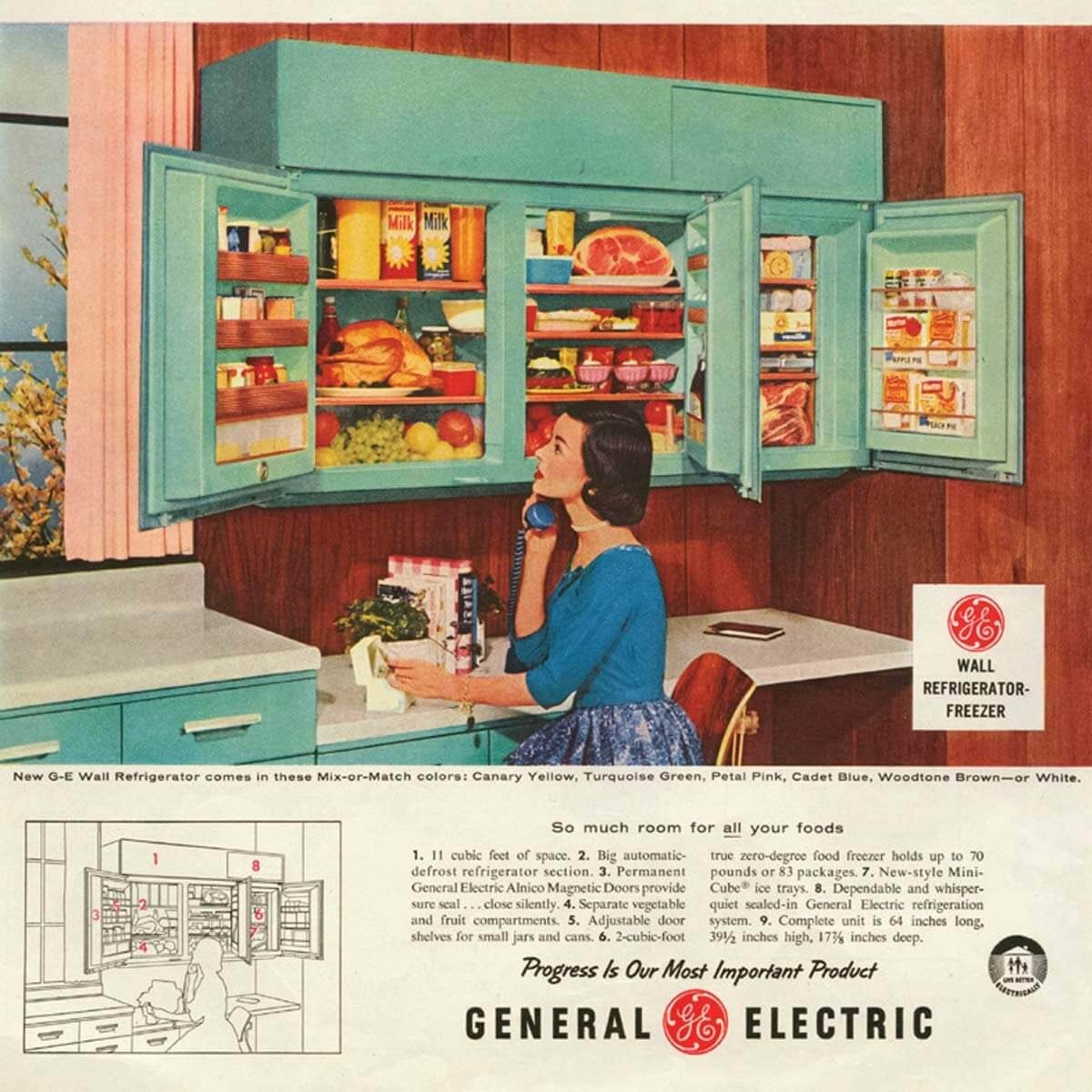

Major appliance manufacturer General Electric launched a number of industry firsts in the mid-'50s while advertising its products' modern appeal. The GE Wonder Kitchen featured a built-in range, dishwasher, disposal, and washer and dryer under a single countertop. The sleek wall-mount, side-by-side refrigerator/freezer, right, has the look of kitchen cabinetry.

Bursts of color

As bright shades debuted in 1950s kitchens, cooks could now choose appliances in hues of yellow, pink, blue or turquoise to help modernize their family gathering spot.

Working for you

This colorful kitchen is worth your minute of study. There are no wasted steps in serving meals or in cleaning up: A drop-leaf cart carries food from range and refrigerator to table in one trip. The folding doors of the dish cabinet open easily to place contents within easy reach. Featured in the House Beautiful April 1957 issue.

Mint green accent

This 1950s magazine illustration features a mint green oven that matches the slanted rafters, a polished brass pendant light, and elegant wood cabinetry. Note the white-brick wall – a predecessor to the metro tile – and the trendy gold-colored hardware, which can be seen in many modern homes today.

Domestic bliss

This magazine illustration features powder-blue units and contrasting copper-colored appliances. Note the archetypal sunburst clock, the under-cabinet dining nook, and of course the beaming housewife. An early ancestor of the industrial trend, the image reveals the roots of the exposed brick wall.

Pink is everywhere

It’s the 1950s. The war is over, and the United States is enjoying a wave of unprecedented prosperity. Millions of GIs returned, eager for the comforts of home that they had been missing, and everyone settled down to a kind of nationwide nesting. Record numbers of homes were being built in the newly developed suburbs, and the center of all those homes was the kitchen.