Holiday Cheer Throughout the Decades

/For its first century as a city, San Francisco celebrated the holidays with all the energy it could muster. With each tragedy, war and building boom, the holiday spirit seemed to be growing along with the city. The traditions arguably peaked in the 1950s, when optimism, good financial times and hometown spirit combined for some of the most magical Decembers in San Francisco. Through the good and bad times, San Francisco has always embraced the holiday spirit as depicted in the stories and quotes in this column.

Late 1800s

“Yesterday was (meteorologically speaking) another dismal day, with drenching rain and miry street crossings, suggesting anything but cheerful reflections,” The Chronicle reported in 1869. “Yet the streets were full of men and women whose countenance showed no sympathy with the untoward surroundings.”

By the 1870s, the newspaper was advertising multiple Christmas tree lots in San Francisco, including one owner who boasted he was cutting down the best of the “virgin redwood forest” in Marin County. There were early reports of charity, and boardinghouses served roast beef and plum pudding to miners and other men who were away from their families.

Jewish families were rising in economic and philanthropic clout at the end of the 19th century, and the city’s holiday celebrations started to reflect their traditions. The earliest coverage of Hanukkah was respectful (if not well researched) and never divisive.

The first Chronicle article to use the word Hanukkah, in 1897, was headlined “Hebrew Festival of Lights Observed — Children Assemble to Light a Taper.”

“‘The Festival of Lights,’ a pretty biblical celebration, replete with religious sentiment and forcibly recalling a heroic period of Hebrew history, was inaugurated yesterday at the Mission-Sabbath school,” The Chronicle wrote.

Rabbi Jacob Voorsanger’s speech to the congregation was also excerpted, and seemed to be aimed at the gentiles in the crowd as much as the Jews: “Maccabee was a hero, fighting for liberty as George Washington fought. The lesson of the Hebrew hero should grow strong in your hearts, making you faithful Jews and loyal citizens. Yours is a beautiful religion. You should be proud of being Hebrews. If you are true to your country your country will be benefited in good men and women.”

Early 1900s

“Who could believe that there would be another merry Christmas in San Francisco for many a year?” The Chronicle editorial staff wrote after the 1906 earthquake and fire. “And yet the first return of this day is the merriest Christmas of all. It is something to think of. It is something to be proud of. It is something to pass on to our children and our children’s children, as a glorious exemplification of the way in which a heroic people meet a great crisis.”

The April 18, 1906, earthquake and fire destroyed most of downtown, and many other businesses and homes. But if anything the holiday spirit grew in its wake. In the years that followed, as the city rebuilt and prepared for the Panama-Pacific International Exhibition of 1915, new traditions seemed to be added in the city every year.

In 1907, different charities decorated 12 large outdoor trees in San Francisco, with the aim of having one within walking distance of children in every city neighborhood. (The Chronicle called it “a perfect orgy of Christmas tree-ing.”)

1920s

“There will be half-orphans there that are boarded with their mothers, whole orphans, and children who were sick or poor or abandoned,” an unnamed reporter wrote of one tree celebration on Nob Hill. “There will be children of all ages up to 14, and of all sizes and colors and creeds and nationalities, and all interested in Santa and sharing the Christmas joy.”

Radio in the 1920s added hype to the holiday; many stations were sponsored by department stores, bringing more commercialization to the season. The KPO “Christmas party” on Dec. 24, 1929, included Christmas carols, a live visit from Santa Claus and “a Bavarian yodel number with jingle-bell accompaniment.”

1930s

“Santa Claus again is making preparations for a visit to San Francisco, according to a radio-gram just received from the North Pole,” read one 1932 story, which ran in the news section next to articles about real-life crimes.”

By the 1930s, Chronicle reporters were taking the ethically questionable (but well-intentioned) approach of reporting about Santa Claus as if they had interviewed him, or had a correspondent embedded in his workshop full of elves.

1940s

“Christmas in San Francisco is quickly assuming all the traditional holiday color,” The Chronicle reported in 1949. “The city’s fire stations, normally prosaic brick structures with cavernous entrances, now have charmed themselves into Christmas wonderlands for the second year.”

The end of World War II brought more families, more money and an all-time high for holiday revelry. Macy’s took its window displays to new levels of memorable. The City of Paris Christmas tree, rising at least four stories in the middle of the Union Square store, was a holiday destination for generations of children.

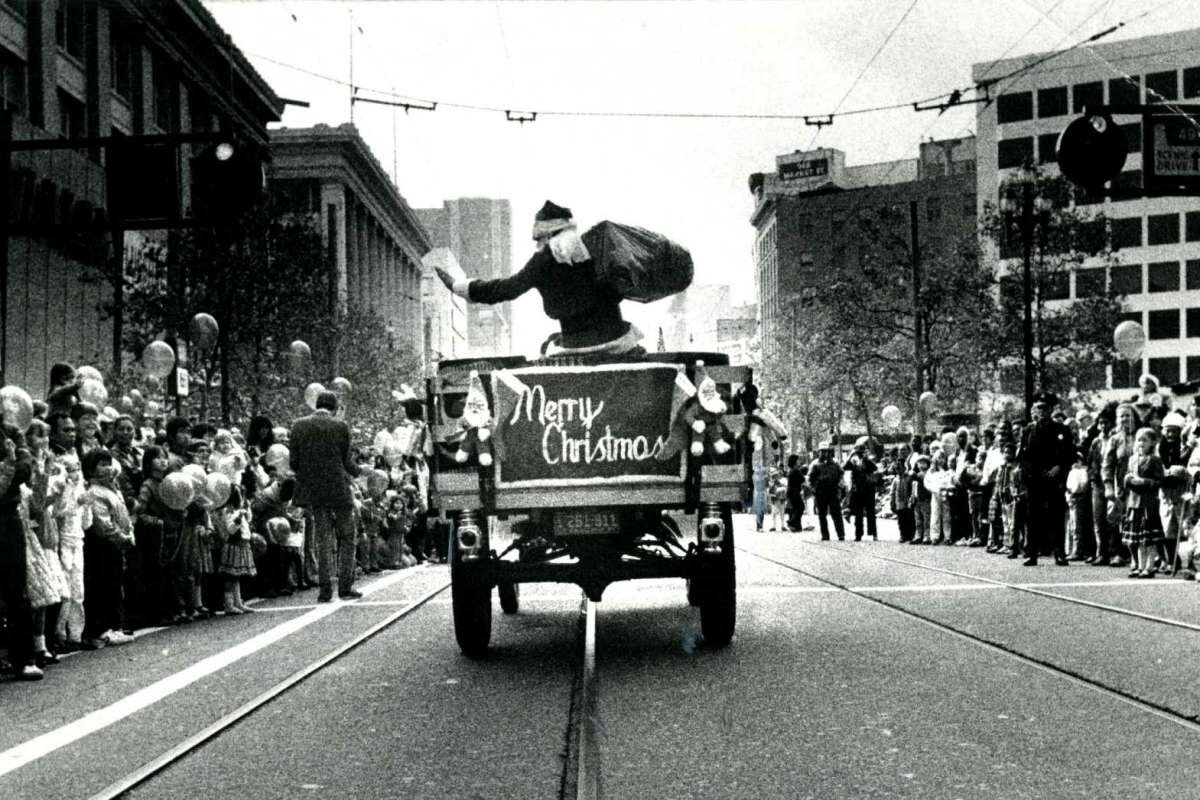

But the arrival of Santa Claus down Market Street was the focal point of the holiday excitement. In an era before Elvis started shaking his hips and before Willie Mays came to town, Santa Claus was the biggest rock star in the city. Thousands of children would line the streets as Santa arrived at the Emporium by carriage, helicopter and (most San Francisco of all) on the top of a Muni bus.

1950s

“He appeared at the brink of Nob Hill, sitting in a chimney atop Muni’s No. 514, filled with a throng of happy children and an engineer at the controls of the public address system to broadcast Santa’s cheery, preseason greetings,” The Chronicle reported in 1952, on the eve of an election. “A torrent of multicolored balloons spilled from the top windows of the Emporium, and as he paused, Terry Gould, a Cub Scout of Pack 30 presented Santa with an ‘absentee ballot.’ Then the crowd, following behind Santa, surged into the store and up to The Emporium’s Christmas roof playground.”

Possibly the greatest holiday tradition in San Francisco history, which lasted just three years from 1948 to 1950, was the decorating of the city’s firehouses. San Francisco Fire Department stations transformed their facades — turning the buildings into presents and toy factories and giant letters to Santa. Neighbors pitched in, building props and sewing costumes. Muni offered San Francisco children free tours of the finished product.

It was more than a playground. The Emporium had rides on the roof, including a carousel and giant slides. One year, the store on Market between Fourth and Fifth streets used a giant crane to lift a cable car to the top of the building.

The tradition ended, in true San Francisco fashion, with a battle between the unions and the city. After the citizens failed to pass a proposition that included a firefighter pay raise, the organizers decided decorating fire stations was too expensive. There were no fire stations decorated in 1951.

1960s and 70s

Santa Claus continued his parades through the 1960s and 1970s, but with television, “Star Wars” and arcade games stealing the hearts and imaginations of children, the sight of St. Nick became less of a novelty. The first mention of Kwanzaa was in 1977; once again treated respectfully, even if the celebration honoring African American culture was oversimplified.

The new Transamerica Pyramid in the 1970s transformed itself into a large red-and-green Christmas tree, and then stopped, according to Herb Caen, because of the high cost. There’s a bright light on top of the Pyramid now, and smaller buildings downtown have added colored lighting. But it’s all hard to see anyway, because newer construction blocks the view.

Today

Progressive change was arguably positive for the city, but not as good for the San Francisco holiday spirit. Families have traditions, but there are fewer celebrations that unite San Francisco as a city. Union Square still has an ice rink. The San Francisco City Hall Christmas tree still exists (now named the more politically correct World Tree of Hope).

One of the last great traditions is one of the best: The Embarcadero Center rims each of its four buildings with lights, looking like a pile of shining presents near the waterfront. Take a ferry to Alameda or Larkspur, and you can pretend San Francisco is still embracing the old days, when Christmas in the city was the most important day of the year.

Or you can just read the old clippings. There are messages from previous generations, practically begging us not to forget to count our blessings and celebrate the season.

Special thanks to the Chronicle and Peter Hartlaub. These are excerpts from an article he wrote in 2015.